Monday, November 29, 2010

Humans have been placing their deceased loved ones in coffins for centuries. The word "coffin" is ultimately derived from the Greek word ko-pi-na ,(basket) which as a word appeared in manuscripts as far back as 1300 B.C.!

In the US, the design has stayed relatively the same over the years, except for that brief time in the 1800's that people were afraid of being buried alive and a crop of "safety coffins" popped up.

The same is not true in Ghana, Africa, where for the last 60 years the Ga tribe in the coastal region of Ghana have celebrated an individual's life by designing custom coffins.

When I say custom coffin I do not mean painting a traditional coffin in personalized colors or designs as the company Colorful Coffins in the UK, or Happy Coffins in Singapore does. Although these coffins are beautiful and individualized, they still hold to the traditional Coffin form.

When I say custom coffin I do not mean painting a traditional coffin in personalized colors or designs as the company Colorful Coffins in the UK, or Happy Coffins in Singapore does. Although these coffins are beautiful and individualized, they still hold to the traditional Coffin form.

In Ghana, however, "custom" implies bold and different, as a handful of wood workers have created a unique craft, actually molding the wood into individual objects that represent the deceased's life. This can range from a soda bottle, seashell, fish, or shoe to represent an item the person sold for a living. Or the coffin may be a symbol of something loved, like a cigarette, Mercedes, airplane or ice cream bar.

In Ghana, however, "custom" implies bold and different, as a handful of wood workers have created a unique craft, actually molding the wood into individual objects that represent the deceased's life. This can range from a soda bottle, seashell, fish, or shoe to represent an item the person sold for a living. Or the coffin may be a symbol of something loved, like a cigarette, Mercedes, airplane or ice cream bar.

The colorful coffins take weeks to months to prepare and can cost a year's salary for a Ghana resident. If the deceased hadn't planned ahead enough for the coffin to be ready- the body sometimes must be refrigerated the length of time it takes to finish. Other delays can come with family disputes on what item should actually represent the deceased.

The colorful coffins take weeks to months to prepare and can cost a year's salary for a Ghana resident. If the deceased hadn't planned ahead enough for the coffin to be ready- the body sometimes must be refrigerated the length of time it takes to finish. Other delays can come with family disputes on what item should actually represent the deceased.

They say that more and more foreigners are purchasing these type of coffins, thought whether the purchase is purely for art or if this trend is beginning to catch on for actual burial practices is unknown. In case you are interested eShopAfrica actually offers the Ga coffins for purchase on-line and shipped to your door. (You may also enjoy seeing other ideas)

They say that more and more foreigners are purchasing these type of coffins, thought whether the purchase is purely for art or if this trend is beginning to catch on for actual burial practices is unknown. In case you are interested eShopAfrica actually offers the Ga coffins for purchase on-line and shipped to your door. (You may also enjoy seeing other ideas)

So, what do you think? Does the idea of personalizing your coffin as the other two companies listed above do, appeal to you? Do you think the idea of a over-sized wooden object as a coffin will catch on in the US?

Monday, November 29, 2010 by Amy Clarkson · 3

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

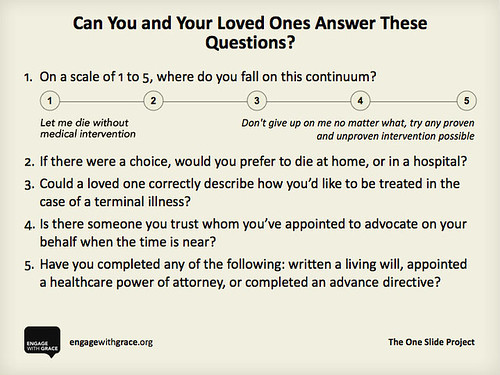

For three years running now, many of us bloggers have participated in what we’ve called a “blog rally” to promote Engage With Grace – a movement aimed at making sure all of us understand, communicate, and have honored our end-of-life wishes.

The rally is timed to coincide with a weekend when most of us are with the very people with whom we should be having these unbelievably important conversations – our closest friends and family.

At the heart of Engage With Grace are five questions designed to get the conversation about end-of-life started. We’ve included them at the end of this post. They’re not easy questions, but they are important -- and believe it or not, most people find they actually enjoy discussing their answers with loved ones. The key is having the conversation before it’s too late.

This past year has done so much to support our mission to get more and more people talking about their end-of-life wishes. We’ve heard stories with happy endings … and stories with endings that could’ve (and should’ve) been better. We’ve stared down political opposition. We’ve supported each other’s efforts. And we’ve helped make this a topic of national importance.

So in the spirit of the upcoming Thanksgiving weekend, we’d like to highlight some things for which we’re grateful.

Thank you to Atul Gawande for writing such a fiercely intelligent and compelling piece on “letting go”– it is a work of art, and a must read.

Thank you to whomever perpetuated the myth of “death panels” for putting a fine point on all the things we don’t stand for, and in the process, shining a light on the right we all have to live our lives with intent – right through to the end.

Thank you to TEDMED for letting us share our story and our vision.

And of course, thank you to everyone who has taken this topic so seriously, and to all who have done so much to spread the word, including sharing The One Slide.

We share our thanks with you, and we ask that you share this slide with your family, friends, and followers. Know the answers for yourself, know the answers for your loved ones, and appoint an advocate who can make sure those wishes get honored – it’s something we think you’ll be thankful for when it matters most.

Here’s to a holiday filled with joy – and as we engage in conversation with the ones we love, we engage with grace.

To learn more please go to www.engagewithgrace.org. This post was written by Alexandra Drane and the Engage With Grace team.

Wednesday, November 24, 2010 by Christian Sinclair · 0

Monday, November 22, 2010

Ten years ago, Mark Hogancamp was attacked outside of a bar by 5 men. He was badly beaten and nearly died. It took 9 days for him to wake up after the attack and as a result Mark lost most of his memories and had severely impaired motor function. For his own therapy, physical as well as emotional, Mark created his own world which he calls Marwencol.

Ten years ago, Mark Hogancamp was attacked outside of a bar by 5 men. He was badly beaten and nearly died. It took 9 days for him to wake up after the attack and as a result Mark lost most of his memories and had severely impaired motor function. For his own therapy, physical as well as emotional, Mark created his own world which he calls Marwencol.

Marwencol is a fictional 1/6 scale WWII era Belgium town. The town's inhabitants are all dolls. Mark has created a doll for himself (named Hogie) and many of his family and friends are also represented. Mark poses the dolls in various scenes and then takes photos to tell the story. His storyline: Nazis, romance, torture, a time traveling witch (?).

His dolls and props are made to be very realistic. To enhance this effect, Mark actually places his characters in his model jeep and pulls it along side him when he takes a walk, giving them authentic wear and tear.

A local photographer saw Mark walking with his jeep and asked Mark what he was doing. Mark then shared his photographs. This discovery has led to a lot of publicity for Marwencol, including an art show in New York and now a documentary. Unfortunately the documentary is only playing in a select few cities nation wide and Kansas City is not one of them. But the trailer gives you a good feel (below).

So my question, after looking through some of the Marwencol photos is, when does this therapy cross the line and become pathological? The photos are wonderful. The scenes Mark puts together are amazingly life-like. But many of the scenes are about murder and torture. Hogie's wedding scene had dead Nazis hung up in the back ground. I just couldn't help but think that the Nazis are perhaps the 5 men who took his life away. Is he really just reliving his trauma over and over rather than adjusting his life to move past it? Making his make believe world exactly what he wants his real world to be?

On the other hand, maybe this is giving him the only life that he would be able to have. Maybe without it he wouldn't have a reason to go on after the terrible trauma he went through. If living in his own world is the only thing that is keeping him going, who am I to say that it's bad?

The Marwencol website gallery posts some of Mark's photos along with his captions to tell the stories. In the last postings, Hogie and his wife Anna (apparently in the image of his ex-wife) have been assassinated. The following is the collected captions of this most recent installment. I leave you with this because I think it says a lot.

"Meanwhile the SS are downstairs having drinks. They're celebrating that the King and Queen of Marwencol are dead. Now it's easy to take over the townspeople-they don't have leaders or anything. Then Anna and I stick our heads over the railing of the balcony. We look down at the Nazis down there. And they look up and they're floored. And Anna and I hug. And the Nazis realize that they can't kill me. They can't kill Anna or I because we're going to live forever. We're immortal. I won."

Monday, November 22, 2010 by Amber Wollesen, MD · 5

Monday, November 15, 2010

One of the things I enjoy about "the arts" is the ability to continually stimulate more art. Art imitates life, life imitates art, and art even imitates art.

One of the things I enjoy about "the arts" is the ability to continually stimulate more art. Art imitates life, life imitates art, and art even imitates art.

Monday, November 15, 2010 by Amy Clarkson · 0

Monday, November 8, 2010

My Life Without Me has been on my To See movie list for a long time. This weekend I finally had the opportunity.

My Life Without Me has been on my To See movie list for a long time. This weekend I finally had the opportunity.

Ann is 23 years old. She lives in a trailer in her mother's back yard with her husband and two young girls. She works nights cleaning the university. After having a fainting spell at home, she discovers that she has ovarian tumors that have spread to her stomach and liver. She is given about 2-3 months to live. One of the first things she does is sit and make a list of all the things she wants to do before she dies.

1. Tell my daughters I love them several times.

2. Find Don a new wife who the girls like.

3. Record birthday messages for the girls for every year until they're 18.

4. Go to Whalebay Beach together and have a big picnic.

5. Smoke and drink as much as I want.

6. Say what I'm thinking.

7. Make love with other men to see what it's like.

8. Make someone fall in love with me.

9. Go and see Dad in Jail.

10. Get false nails. And do something with my hair.

She never tells anyone about her diagnosis. She says she does this as a gift for her husband and children as she doesn't want their last memories of her to be doctor appointments and hospitals. For the same reason she refuses any treatments or further tests. She works to complete her list, while making tapes for all of her loved ones to explain her choices and offer some final words.

She has a unique relationship with her doctor, Dr. Thompson. When he is telling her the bad news about her cancer, he sits beside her in a waiting room chair. He admits to her that he has to sit beside her because he can never look someone in the eye when he tells them they are going to die. In the end, Ann entrusts him with all of the tapes she made for her daughters as she knows he will remember to send them. He agrees to do this as long as Ann will continue to come and see him weekly, saying "Dying is not as easy as it looks, you know, but there's no need for you to have to feel terrible all the time."

The story is often run through Ann's inner monologues, what she is thinking about life and death as she does the grocery shopping, or walks down a busy street. Below is from the beginning of the movie as she is standing out in the rain.

"This is you. Eyes closed, out in the rain. You never thought you'd be doing something like this, you never saw yourself as, I don't know how you'd describe it... As like one of those people who like looking up at the moon, who spend hours gazing at the waves or the sunset or... I guess you know the kind of people I'm talking about. Maybe you don't. Anyway, you kind of like being like this, fighting the cold, feeling the water seep through your shirt and getting through your skin. And the feel of the ground growing soft beneath your feet. And the smell. And the sound of the rain hitting the leaves. All the things they talked about in the books you haven't read. This is you, who would have guessed it? You."

At then end the film, Ann lies in bed watching her neighbor (also named Ann) joyfully interact with her husband and children as the neighbor helps them make dinner. She tells them she is bed suffering from a bad case of anemia.

"You pray that this will be your life without you. You pray that the girls will love this woman who has the same name as you and that your husband will end up loving her too. And that they can live in the house next door and the girls can play dollhouses in the trailer and barely remember their mother who used to sleep during the day and take them on raft rides in bed. You pray that they will have moments of happiness so intense that all their problems will seem insignificant in comparison. You don't know who or what you're praying to but you pray. You don't even regret the life you're not going to have because by then you'll be dead and the dead don't feel anything. Not even regret."

This is a very sad but beautiful movie. (I will admit that I may have shed a couple tears at the end.) As Ann moves through her last days, you really get to feel you know her. It's an interesting perspective on dying young and poor. For what little she has, Ann accomplishes a lot in her last few days and weeks.

Monday, November 8, 2010 by Amber Wollesen, MD · 7

Monday, November 1, 2010

Dr.Chen is a surgeon who does both liver transplants and liver cancer surgery. Most recently on faculty of UCLA department of surgery, she speaks nationally and writes a column for The New York Times.

Her book, as the title implies is a autobiographical reflection of her experiences regarding death; beginning in medical school and moving through various training periods. We in palliative care, of course, deal with death frequently, thus reading this book you will surely find things that resonate with you as well as things that frustrate you.

Her writing style is very engaging in its authenticity and narrative form. I read about patients that could easily have been people I have taken care of in my own training. The honest insight into her thoughts is refreshing. I enjoyed watching the transformation of her own avoidance of death, to a timid acceptance of death.

There are fundamental ideologies that she depicts that are very entrenched in our medical system as the following quotes illustrate:

"Along the way, then, we learn not only to avoid but also to define death as the result of errors, imperfect technique, and poor judgment. Death is no longer a natural event but a ritual gone awry.....By evading death, we miss one of the best opportunities for us to learn how "to doctor" because dealing with the dying allows us to nurture our best humanistic tendencies" (p95)

"Over time we come to believe so deeply that sublimating our fear of death makes us better doctors that some of us will skip around the very word during our conversations with terminal patients."(p205)

She records poignant questions around the idea of when to stop curative measures, and when care becomes more about doing something "to" someone instead of "for" someone in vignettes about Sam, a young man with brain mets and Max, and infant born with gastroschisis who required a liver and bowel transplant. Having had these conversations with people, I found myself wanting to answer Sam's wife when she wonders, "When do you know....when you have done enough?" (p145)

She records poignant questions around the idea of when to stop curative measures, and when care becomes more about doing something "to" someone instead of "for" someone in vignettes about Sam, a young man with brain mets and Max, and infant born with gastroschisis who required a liver and bowel transplant. Having had these conversations with people, I found myself wanting to answer Sam's wife when she wonders, "When do you know....when you have done enough?" (p145)"Your liver is struggling" I said. But Franks's liver was not struggling; it was failing. I knew that in the next few days he would likely fall into a coma and die....I could not bring myself to describe that outcome." (p187)

She ends her conversation with a hopeful remark about checking the labs tomorrow to see if they improve.

It was moments such as those I wanted to jump into the pages and say "No...you can do it... you can be honest to Frank in a compassionate way!"

The final story is I suppose the transformation Dr. Chen makes. She recounts a patient with cholangiocarcinoma who wanted to die at home. As he gets sicker and she realizes his prognosis, she allows him the decision to decide his outcome, whether to head to the ICU for more invasive interventions or head home to die. There is no surprise that he opts to go home. I found it interesting that still, in the final paragraphs of the book that she continued to struggle with his death. She closes out the book with these words:

If I had one wish about the book, I would have hoped to read more about palliative care. In so many of these examples I longed for their presence to offer guidance in communication and discussions about goals. While it is refreshing that Dr. Chen is being transformed as a physician to have these talks in a compassionate way, the truth is, most health care workers still find themselves trapped in the ideologies about death and prognosis discussed in the beginning chapters. While it is lovely to envision a medical education system that trains up physicians comfortable with death, it remains an ideal at best. In the meantime, let's get those palliative care teams involved!

Overall, this is a book I would absolutely recommend; an engaging narrative that we can all identify with!

Monday, November 1, 2010 by Amy Clarkson · 3